CS Executive JIGL – Constitution Of India

Writ jurisdiction

Under Article 226 of the Constitution, the High Court has the power to issue not only writs of certiorari, prohibition and mandamus, but also other writs, directions and orders.

The Indian High Court has jurisdiction to issue necessary directions and orders to ensure justice and equity. Moreover, this right is not restricted, but spreads to administrative action and judicial or quasi-judicial action also.

When the Supreme Court issues writs under Article 32 of the Constitution, they are mainly for the enforcement of fundamental rights mentioned in the Constitution itself.

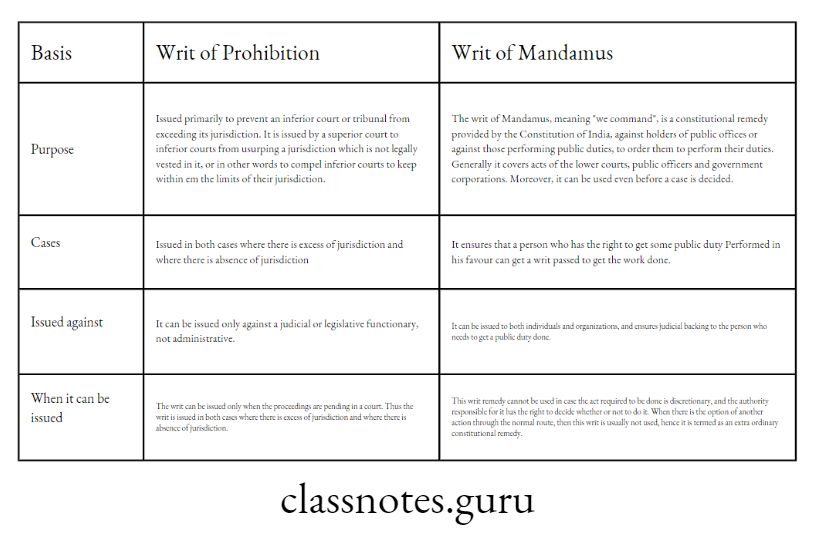

The Writ of Prohibition

The writ of prohibition is issued primarily to prevent an inferior court or tribunal from exceeding its jurisdiction. It is issued by a superior court to inferior courts from usurping a jurisdiction which is not legally vested in it, or in other words to compel inferior courts to keep within the limits of their jurisdiction.

Thus the writ is issued in both cases where there is excess of jurisdiction and where there is absence of jurisdiction (S. Govind Menon vs. union of India, AIR 1967 SC 1274 The writ can be issued only when the proceedings are pending in a court. It can be issued only against a judicial or legislative functionary, not administrative.

The Writ of Mandamus

On the other hand, the writ of Mandamus, meaning “we command”, is a constitutional remedy provided by the Constitution of India, against holders of public offices or against those performing public duties, to order them to perform their duties.

It can be issued to both individuals and organizations, and ensures judicial backing to the person who needs to get a public duty done.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus

It is passed to ensure that a person who is confined without a legal cause being given gets justice. This writ orders the authority confining the person to give proper reasons for doing so.

Learn and Read More CS Executive JIGL Question and Answers

Colourable legislation

The doctrine of colourable legislation is relevant only in connection with the question of legislative competency. Objections based on colourable legislation have relevance only in situations when the power is restricted to particular topics, and an attempt is made to escape legal fetters imposed on its powers by resorting to forms of legislation calculated to mask the real subject matter.

Federal system

A federal system is one where the powers and duties are divided between a unified central authority and the different states of the nation. Items of national importance like defence, railways, post and telegraph, foreign affairs, citizenship etc. are included in the Union list and items of regional or local importance like agriculture, law and order, health etc are placed in the state list.

Unitary system

A unitary system is one where the powers and functions are centralized. In India, this happens in times of emergencies, when the Union can make rules in relation to state matters too.

State

The definition of ‘State’ has been included in Article 12 of the Constitution of India. It includes not only entities termed as ‘state’ but also those termed as ‘state instrumentalities’. It includes the government and the parliament of the nation and of every state, local and other authorities like the municipalities, district boards, and any other instrumentality of state, including corporations, government departments and state monopolies.

Delegated legislation

Delegated legislation includes in its folds that part of the power of the legislatures that they could exercise, but which has been delegated because of paucity of time and overloading of work. This leads to better functionality and saving of time.

Conditional legislation

That which is bound by the conditions prescribed, following which the statute comes into play.

Subordinate legislation

This type is subordinate to the supreme legislation.

Supplementary legislation

This is in addition to the main legislation; it only adds to the main one.

Classification

Classification means segregating people into groups according to a commonly identified feature, viz income, geographical location, gender, etc. so that their special needs can better be catered to and their legal rights ensured.

By itself, classification is not against the Constitution. Rather, it helps in upholding the principle of equality. In doing so, even if the class has a single individual in it, it will still be a valid class.

The Doctrine of Severability

This Doctrine is contained in Article 13 of the Constitution of India. According to this doctrine, the part of a statute which is not compatible with the fundamental rights provided for in the Constitution will be severed and declared invalid.

This helps to maintain both constitutionality and saves the statutes from being struck down completely. The rest of the act that is allowed to exist can operate separately.

Preventive detention

‘Preventive detention’ implies the detention of a person without trial in cases where the evidence before the authority is not enough to make out a fully drawn legal charge or to secure the conviction of the detenue by legal proof, but is sufficient enough to justify his detention.

Doctrine of pith and substance

Applying the pith and substance rule, we have to reach to the core of the act, i.e., try to learn what the act endeavour to legislate in the first place. If that is valid, then the act upholds and is allowed to be functional.

Law

As per Article 13

Doctrine of eclipse

The Doctrine of Eclipse is a part of Article 13 of the Constitution of India. It helps in empowering the fundamental rights.

According to this doctrine, if there is any act prevailing from before the pre-Constitution days, and it contains something that is against the Constitution, the act will not become redundant, but will be eclipsed or become dormant to that extent till the Constitution is amended so it can be operative again.

This saves parliamentary laws from being scrapped and remade, and whenever such eclipse is removed, the law is operative again from the date of such removal.

Doctrine of waiver of rights

The doctrine of waiver of rights is based on the premise that a person is his best judge and that he has the liberty to waive the enjoyment of such rights as are conferred on him by the State.

However, the person must have the knowledge of his rights and that the waiver should be voluntary. The doctrine was discussed in Basheshar Nath v. I.T.

Commissioner, A.I.R. 1959 S.C. 149, where the majority expressed its view against the waiver of fundamental rights.

It was held that it was not open to citizens to waive any of fundamental rights. Any person aggrieved by the consequence of the exercise of any discriminatory power, could be heard to complain against it.

Single person law

Even if a class has a single person constituting it, it is not invalid. A law may be constitutional, even though it relates to a single individual, if that single individual is treated as a class by himself on some peculiar circumstances. (Charanjit Lal Chowdhary v. Union of India)

Legislative Classification

A right conferred on persons that they shall not be denied equal protection of the laws does not mean the protection of the same laws for all. It is here that the doctrine of classification steps in and gives content and significance to the guarantee of the equal protection of the laws.

To separate persons similarly situated from those who are not, legislative classification or distinction is made carefully between the persons who are and who are not similarly situated.

Reasonable restrictions

Article 19 of the Constitution of India guaranteed to the citizens the following six freedoms:

- Freedom of speech and expression.

- Freedom of assemble peaceably and without arms.

- Freedom of associations and unions.

- Freedom to move freely throughout the territory of India. d (

- Freedom to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India.

- Freedom to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business.

Restrictions: These freedoms are not absolute and are subject to reasonable restrictions. The State has the power, to make laws imposing reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the above rights in the interest of the following:

- The sovereignty and integrity of India.

- The security of the State.

- Friendly relations with foreign States.

- Public order.

- Decency or morality.

- Contempt of court.

- Defamation.

- Incitement to an offence.

- Prescribing professional and technical qualifications necessary for practicing any profession or carrying on any occupation, trade or business.

Double jeopardy

Jeopardy means punishment. Article 20(2) of Constitution of India incorporates prohibition against double jeopardy. The object of this provision is to avoid the harassment which must be caused to a person for successive criminal proceedings where only one crime has been committed.

Protection against ex-post facto laws

According to Article 20(1), no one shall be convicted of any offence except for violation of a law that made the act committed an offence. Nor can a penalty greater than that which might have been inflicted under the law in force at the time of the commission of the offence be charged for the offence.

Ex-post facto laws

These are laws which punish what had been lawful when done. The Constitution protects anyone who had committed an act earlier when the act was not punishable from being punished with retrospective effect.

If a particular act was not an offence according to the law at the time when the person did that act, then he cannot be convicted under a law which with retrospective declares that act as an offence.

For example, something done in 2000 which was not an offence then under any law cannot be declared as an offence under a law made in 2018 giving retrospective validity and adding applicability to it from a back date, say from 2000.

Similarly, the penalties for an offence too, cannot be enhanced with retrospective effect, so as to bring more punishment to bear upon someone who had committed an act against that law.

CS Executive JIGL – Constitution Of India Short Notes

Question 1: Write a short note on writ of ‘Quo Warranto’.

Answer:

The writ of Quo Warranto enables enquiry into the legality of the claim which a person asserts, to an office or franchise and to oust him from such position if he is a usurper. The holder of the office has to show to the court under what authority he holds the office. It is issued when:

- the office is public and of a substantive nature,

- created by statute or by the Constitution itself, and

- the respondent has asserted his claim to the office. It can be issued even though he has not assumed the charge of the office.

The fundamental basis of the proceeding of Quo Warranto is that the public has an interest to see that an unlawful claimant does not usurp a public office. It is a discretionary remedy which the court may grant or refuse. Space to write important points for revision

CS Executive JIGL – Constitution Of India Distinguish Between

Question 2: Distinguish between the following:

‘Writ of prohibition’ and ‘writ of mandamus.’

Answer:

CS Executive JIGL – Constitution Of India Descriptive Questions

Question:

- What is the scope of Article 14 of the Constitution of India? To what extent is it correct to say that Article 14 forbids class legislation, but does not forbid classification?

- Discuss the fundamental duties imposed on citizens of India.

Answer :

1. This Article 14 of the Constitution of India is about equality before law. This article envisages equality between equals, i.e., those equal in the eyes of law have to be treated equally. A direct corollary of this article is that it is not possible to have different rules for people belonging to the same class.

Therefore, it is possible to have classification but not class legislation under the Constitution of India. Classification would be valid if it fulfils the following tests

- There should be valid factors distinguishing one group from another, while making rules for one group and not for another.

- The differences should be created to achieve some objective enshrined in the act.

- There should be valid bases for classification..

Even if a class has a single person constituting it, it is not invalid. Moreover, the person who says that a classification is invalid has to prove so.

This right is enshrined in Article 14 under Right of Equality as provided In the Constitution of India. The equality before law implies equal protection of the laws and that all persons are equal in the eyes of the law; if two persons are similar as far as their situation is concerned; they will be treated as equal in law.

‘Equal protection of the laws’ implies that all persons who are equal in the eyes of the law will receive same treatment. This article involves the use of classification for the purpose of better-providing equality.

Classification means segregating people into groups according to a commonly identified feature, viz income, geographical location, gender, etc. so that their special needs can better be catered to and their legal rights ensured.

By itself, classification is not against the Constitution. Rather, it helps in upholding the principle of equality. In doing so, even if the class has a single individual in it, it will still be a valid class.

For example, if the Constitution foresees the segregation of backward classes, the desire here is to better accommodate their needs; this is discrimination in favour, not discrimination against anyone.

This in itself means that discrimination in order to make the conditions of a class better is allowed, because this in itself upholds the very foundations of the Constitution and is hence allowed.

2. The 42nd Amendment Act passed in 1976 added the Fundamental Duties of citizens to the Constitution. They are given in Article 51-A of the constitution.

They include the addition made by the 86th constitutional amendment in 2002, which enjoins every citizen, “who is a parent or guardian, to provide opportunities for education to his child or, as the case may be, ward between the age of six and fourteen years”.

These are treated like moral obligations of the citizens of India. The important features of Fundamental Duties are

- They are non-justiciable.

- They cover both citizens and the State.

- They ensure equality of individuals.

They help in maintaining the environment and public property, to develop “scientific temper”, to abjure violence, to strive towards excellence and to provide free and compulsory education.

They develop respect towards the nation and its symbols, and to cherish the heritage and secure the defence of India.

The basic Fundamental Duties are –

To abide by the Constitution and respect its ideals and institutions, the National Flag and the National Anthem. To cherish and follow the noble ideals which inspired our national

struggle for freedom.

To uphold and protect the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India. To defend the country and render national service when called upon to do so.

To promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood amongst all the people of India transcending religious, linguistic and regional or sectional diversities; to renounce practices derogatory to the dignity of women.

To value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture.

To protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures.

To develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform.

To safeguard public property and to abjure violence.

To strive towards excellence in all spheres of individual and collective activity so that the nation constantly rises to higher levels of endeavor and achievement.

It has to be kept in mind, however, that the Fundamental Duties are not enforceable by writs; their fulfilment can only be ensured by educating the citizens as to their necessity and importance.

Question:

1. Creation of monopoly rights in favour of a person or body of persons to carry on any business prima facie affects the freedom of trade. Can the State create a monopoly in favour of itself? Answer citing case law, if any.

2. Describe in brief the powers of Parliament to make laws on the subjects ( enumerated in the State List. (6 marks)

3. The true place of a preamble in a statute was at one time the subject of conflicting decisions. Is such an opinion still prevailing? Discuss, citing case law. (6 marks)

Answer:

1. Freedom of trade and profession is provided under Article 19 (1) (g) of the Constitution of India. This gives the citizens the right to pursue any trade, profession, business or occupation in any place within India. This right is, however, not absolute. It can be restricted by the State in the following cases

- When the State feels it is essential to do so in the public interest.

- When it is felt that there should be some basic qualifications for any occupation or profession, it can provide so.

- When the State feels that it needs to establish control in some area of trade, occupation or business, so that it can be better tended.

These restrictions shall be considered valid when the conditions of the trade or business restricted at that time justify them, for example, for keeping the price of essential services down. Hence, the State can take over these rights to any extent-from being one of the participants in that trade to being the only one, provided it is justified in doing so.

On behalf of the State it was argued that Article 19(6) of the Constitution indicated, as in its amended state, that the carrying on by the State, or by a corporation owned or controlled by the State, of any trade, business or industry or service, whether to the exclusion, complete or partial, of the citizens or otherwise, was a permissible restriction on an individual’s right of trading.

2. The Parliament can extend the legislative powers given to it by the Constitution to formulate laws under special situations to include certain subjects of the State List. Some of the conditions under which the Parliament may extend its powers include the situations explained below-

In the National Interest (Under Article 249)

Proclamation of Emergency (Article 250) in any state by the President. If two states agree that the Parliament can legally make laws with respect to the two states, then the Parliament can make laws relating to any state or states (Under Article 252) For the implementation of treaties in the international interest of the country (Under Article 253).

Failure of Constitutional Machinery in a State as a result of the inefficiency of a State Legislature, as declared by a proclamation issued by the President (Under Article 356 (1) (b))

Normally both the Union Government and the State Governments operate within the limitations of the powers given to them by the Constitution. They enjoy equal powers to make laws relating to the concurrent list items, which are of general importance such as succession, transfer of property, preventive detention, education, etc.

If there arises a conflict between a law passed by the Union and that passed by one or more State Legislatures, precedence would be given to the law made by the Union Parliament.

However, problem arises when either the Union or a State illegally encroaches upon the powers of the other legislature, or they may arise because the two laws do not coordinate. Only where the legislation is on a matter in the Concurrent List, it becomes important to apply the test of repugnancy and judge which act will apply.

Normally the Union law is given precedence, unless the State has reserved a law for the approval of the President, in which case it will supersede the law made by the Union. However, the Union can at all times cause an alteration or amendment in the law.

3. The preamble of an Act is the introduction or the key to the Act. Although not a part of the Act itself, and so does not perform any legal function, it is a valuable key for understanding the Act and resolving the ambiguities in drafting.

The preamble provides the introduction to the Act and indicates its coverage. Both these views are taken together in comprehending the importance of preambles in interpretation of statutes.

If the statute is clear in itself, the preamble is not resorted to for gaining comprehension; if it is ambiguous or unclear, then the preamble can be used to give a direction to the interpretation.

It thus prescribes an outline to the Act itself, letting the person reading it know what all it includes within its bounds. The preamble specifies the intention behind the making of the act, i.e. what is the mischief that the makers of the act sought to correct.

It can be one of the key starting points when we begin to understand a statute. The next in line is the judgment of the Supreme Court (Girdhari Lal & Sons v. Balbir Nath Mathur) wherein, on the subject of interpretation of Statutes, the Supreme Court had laid down the law as hereunder:

Parliamentary intention may be gathered from several sources. First, of course, it must be gathered from the statute itself, next from the preamble to the statute, next from the Statement of Objects and Reasons, thereafter from parliamentary debates, reports of committees and commissions which preceded the legislation and finally from all legitimate and admissible sources from where there may be light.

Regard must be had to legislative history too. Also, Novartis Ag Represented By It’S … vs Union Of India (Uoi) Through The… on 6 August, 2007. Hamdard Dawakhana (Wakf) Lal… vs Union Of India And Others on 18 December, 1959.

Question: Discuss in brief the doctrine of severability.

Answer:

The Doctrine of Severability: This Doctrine is contained in Article 13 of the Constitution of India. According to this doctrine, the part of a statute which is not compatible with the fundamental rights provided for in the Constitution will be severed and declared invalid.

This helps to maintain both constitutionality and saves the statutes from being struck down completely. The rest of the act that is allowed to exist can operate separately. The only thing to be considered here is whether the leftover portion is enough to still fulfill the objectives of the Act.

This doctrine is a very useful one, used in both contract and common law, as it is useful in saving redundancy of contracts and acts. Under this, Courts construct the meaning of a contract or act by severing the troubling part, if it is severable and only if severability is not possible, the entire act is scrapped (Article 154).

Similarly, the courts have the power to sever an unconstitutional provision in a statute and enforce the remainder of the statute if it can exist without the severed part (Article 155).

This doctrine has been provided to increase the usability of statutory acts and legal contracts, so as to prevent redundancy and to make future use possible. A.K.Gopalan v. State of Madras The Doctrine of Severability.

The Supreme Court ruled that where an Act was partly invalid, if the valid portion was severable from the rest, the valid portion would be maintained, provided that it was sufficient to carry out the purpose of the Act.

Question: Describe the right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions as enshrined in the Constitution of India.

Answer:

Article 30 of the Constitution of India enshrines minority rights. As per the Constitution, minorities include both religious and linguistic minorities. This Article gives the following rights to minorities:

- Right to setup and run educational institutions.

- Right to be duly compensated in case of compulsory acquisition of property of such minority institutions.

- Right against discrimination by the State in giving aid to educational institutions, on the grounds of an institution being governed by a minority faction. Case: T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka.

Question: What is meant by ‘preventive detention’? What are the safeguards available against preventive detention?

Answer:

Preventive detention and safeguards against it:

‘Preventive detention’ implies the detention of a person without trial in cases where the evidence before the authority is not enough to make out a fully drawn legal charge or to secure the conviction of the detenue (detained person) by legal proof, but is sufficient enough to justify his detention.

The aim of preventive detention is to check a person from doing something. that the evidence implies that he might do. Hence, this measure operates simply on the basis of suspicion or belief or probability of something that might be done by the detained person.

In order to prevent abuse of power by the authorities under this provision, the framers of the Constitution provided that if the proper process is not followed, the detention will be deemed to be invalid.

According to Article 22 of the Indian Constitution, no person shall be detained in custody without being informed, as early as possible, of the grounds for such arrest. He shall also be assured of the right to consult and to be defended by a legal practitioner of his choosing.

Upon arrest, such a person is to be produced before the nearest magistrate within a period of twenty-four hours of such arrest. This time is exclusive of the time needed for such journey from the place of arrest to the court of magistrate.

A person can be detained in custody beyond the said period only with the permission of the magistrate, and upon sufficient cause being shown. It is not a punitive but a preventive measure.

While the object of the punitive detention is to punish a person for what he has already done, the object of preventive detention is not to punish a man for having done something but intercept him/her before he/she does it and prevent him/her from doing it.

No offence is proved nor any charges is formulated. The sole justification of such detention is suspicion or reasonable probability of the detenue committing some act likely to cause harm to society or endanger the security of the Government, and not criminal conviction which can only be warranted by legal evidence.

Constitutional Safeguards Against Preventive Detention Laws:

Though the Constitution has recognised the necessity of laws as to preventive detention, it has also provided safeguards to mitigate their harshness by placing fetters on legislative power conferred on the Legislature.

The power of preventive detention is acquiesced in by the Constitution as a necessary evil and therefore hedged in by diverse procedural safeguards to minimise as much as possible the danger of its misuse.

It is for the reason that Article 22 has been given a place in the Chapter on “guaranteed rights”. Clauses (4) to (7) guarantee the following safeguards to a person arrested under preventive detention Law:

- review by Advisory Board;

- grounds of Detention and Representation; and

- composition and Procedure of Advisory Board.

Question: Discuss the test laid down by the Supreme Court of India to determine the entity of “State”, whether it is ‘instrumentality or agency.of State’.

Answer:

‘State’ is defined in Article 12 of the Constitution of India. It includes the Central and the State Governments, the Parliament, the various legislatures and legislative assemblies, all local or other authorities that come under the Territory of India or otherwise under the control of the Indian Government.

In the case of Ajay Hasia vs Khalid Mujib, the Supreme Court prescribed the following test for determining whether an entity is an instrumentality or agency of the State:

- If the entire share capital of the Corporation is held by the Government, it would go a long way towards indicating that the corporation is an instrumentality or agency of the Government.

- Where the financial assistance of the State is so much as to meet almost the entire expenditure of the corporation it would afford some indication of the corporation being impregnated with government character.

- Whether the corporation enjoys a monopoly status which is conferred or protected by the State.

- Existence of deep and pervasive State control may afford an indication that the corporation is a State agency or an instrumentality.

- If the functions of the corporation are of public importance and closely related to government functions, it would be a relevant factor in classifying a corporation as an instrumentality or agency of government.

- If a department of government is transferred to a corporation, it would be ( a strong factor supporting an inference of the corporation being an instrumentality or agency of government.”

In Sukhdev Singh vs Bhagatram and R.D. Shetty vs International Airports Authority, the Supreme Court pointed out that corporations acting as State instrumentality or as agencies of government would be considered to be covered within the definition of ‘State’ because they are subjected to the same limitations in the field of constitutional or administrative law as the government itself, though in the eye of law they would be distinct and independent legal entities.

Question: “Article 20 of the Constitution of India guarantees protection against self-incrimination”. Explain briefly.

Answer:

According to Article 20(3),, “no person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself.” It means that no one can be forced to testify against himself or to incriminate himself.

However, this protection is available to the accused only when the following conditions are fulfilled:

- He must be accused of an offence;

- He is compelled to be a witness; and

- Such a compulsion would cause or force him to give evidence against himself.

So, as per the corollary to this rule, if a person is not an accused or is not in the capacity of a witness when he makes the statement or if the statement is made by him without any compulsion of any sort and also does not result in his making a statement against himself, then he cannot avail of the protection afforded by this rule.

Moreover, such protection is available when the person has been formally accused or is examined as a suspect in a criminal case. It also includes within its ambit witnesses who believe that their statements could expose them to criminal charges.

This is true not only for an ongoing investigation, but also if he fears apprehension in cases other than the one being investigated. [Selvi vs State of Karnataka].

Question: What are the restrictions on right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19 of the Constitution of India?

Answer:

Article 19 of the Constitution of India guaranteed to the citizens the following six freedoms:

- Freedom of speech and expression.

- Freedom of assemble peaceably and without arms.

- Freedom of associations and unions.

- Freedom to move freely throughout the territory of India.

- Freedom to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India.

- Freedom to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business.

Restrictions: These freedoms are not absolute and are subject to reasonable restrictions. The State has the power, to make laws imposing reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the above rights in the interest of the following:

- The Sovereignty and Integrity of India.

- The Security of the State.

- Friendly relations with Foreign States.

- Public order.

- Decency or Morality.

- Contempt of Court.

- Defamation.

- Incitement to an offence.

- Prescribing professional and technical qualifications necessary for practicing any profession or carrying on any occupation, trade or business.

Hence, the freedom of speech and of the expression does not bestow an absolute right to express without any responsibility. The restriction to this is placed by Article 19, Clause (2), of the Indian Constitution that enables the legislature to impose reasonable restrictions on free speech to ensure the following:

- Security of the State – actions intended to overthrow the government, waging of war and rebellion against the government, external aggression or war, etc., may be restrained.

- Friendly relations with Foreign States – to stop the friendly relations of India with other States from being jeopardized.

- Public order – for general peace, safety and tranquility.

- Decency and morality to stop obscenity and indecency from spreading.

- Prevention of Contempt of Court – includes both civil contempt or criminal contempt.

- Prevention against defamation reputation of another is to be stopped. any statement that injures the

- Discouraging incitement to commit an offence, and maintaining sovereignty and integrity of India.

This can, however, be done by a duly enacted law and not by mere executive action. The Constitution, hence, allows reasonable restrictions to be placed on the rights of speech and expression.

The Supreme Court in A K Gopalan vs State of Madras, 1950 has also held that Fundamental Rights are not absolute.

Space to write important points for revision

Question: Discuss ‘the procedure established by law’ under Article 21 of the Constitution of India with decided case laws.

Answer:

The main aim of Article 21 is to ensure personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. This implies that if it is an action initiated by the State only then will the right be available.

Hence, this right works to the exclusion of actions initiated by private individuals, in which case the aggrieved would have to take refuge under Article 226 of the constitution or under general law.

However, where the act of a private individual supported by the state infringes the personal liberty or life of another person, the aggrieved will certainly receive the protection of Article 21.

‘State’ includes government departments, legislature, administration, and local authorities exercising statutory powers etc., but it does not include non-statutory or private bodies having no statutory powers.

Therefore, the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 21 relates only to the acts of State or acts under the authority of the State that are not according to procedure established by law.

‘Right to Life’ relates to the dignity of life, and includes all things that add meaning and dignity to the life of an individual. In the case of Francis Coralie Mullin vs The Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi and Others it was said that: Article 21 requires that no one shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except by procedure established by law and this procedure must be reasonable, fair and just and not arbitrary, whimsical or fanciful.

In another case of Olga Tellis and others vs Bombay Municipal Corporation and others, it was further observed: Just as a malafide act has no existence in the eye of law, even so, unreasonableness vitiates law and procedure alike.

It is therefore essential that the procedure prescribed by law for depriving a person of his fundamental right must conform the norms of justice and fair play. Procedure, which is not just or unfair in the circumstances of a case, attracts the vice of unreasonableness, thereby vitiating the law which prescribes that procedure and consequently, the action taken under it.

The expanded scope of Article 21 has been explained by the Apex Court in the case of Unni Krishnan vs State of A.P. and the Apex Court itself provided the list of some of the rights covered under Article 21 on the basis of earlier pronouncements and some of them are listed below:

- The right to go abroad.

- The right to privacy.

- The right against solitary confinement.

- The right against hand cuffing.

- The right against delayed execution.

- The right to shelter.

- The right against custodial death.

- The right against public hanging.

- Doctors assistance.

- A K Gopalan v. State of Madras: Procedure made by law means a procedure enacted by the law of a state.

- Bachan Singh v State of Punjab: The makers of the Constitution recognized that a person can only be deprived of his life or his personal liberty through a just, fair and reasonable procedure that is duly established by law.]

Question: Explain the freedom of association under the Constitution of India. What reasonable restrictions have been imposed on this freedom under Article 19 of the Constitution of India?

Answer:

According to Article of 19(1) (c) of the Constitution of India, all citizens shall have the right to form associations or unions. The freedom of association includes freedom to hold meeting and to takeout processions without arms.

Right to form associations for unions is also guaranteed so that people are free to have the members entertaining similar views. This right is also, however, subject to reasonable restrictions which the State may impose in the interests of:

- The sovereignty and integrity of India, or

- Public order, or

- Morality.

A question not yet free from doubt is whether the fundamental right to form association also conveys the freedom to deny to form an association. In the case of Tikaramji v.

Uttar Pradesh, AIR 1956 SC 676, the Supreme Court observed that assuming the right to form an association “implies a right not to form an association, it does not follow that the negative right must also be regarded as a fundamental right”.

Question: Article 14 of the Constitution of India says that state shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of laws within the territory of India. Explain it.

Answer:

Article 14 of the Constitution of India provides that “the State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India”.

As is evident, Article 14 guarantees to every person the right to equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws.

The expression ‘equality before the law’ which is borrowed from English Common Law is a declaration of equality of all persons within the territory of India, implying thereby the

absence of any special privilege in favour of any individual.

Every person. whatever be his rank or position is subject to the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts. The expression “the equal protection of the laws” directs that equal protection shall be secured to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction of the Union in the enjoyment of their rights and privileges without favouritism or discrimination.

Article 14 applies to all persons and is not limited to citizens. A corporation, which is a juristic person, is also entitled to the benefit of this Article (Chiranjit Lal Chowdhurary v. Union of India, AIR 1951 SC 41).

The right to equality is also recognised as one of the basic features of the Constitution (Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, AIR 2000 SC 498). A right conferred on persons that they shall not be denied equal protection of the laws does not mean the protection of the same laws for all.

It is here that the doctrine of classification steps in and gives content and significance to the guarantee of the equal protection of the laws. To separate persons similarly situated from those who are not, legislative classification or distinction is made carefully between persons who are and who are not similarly situated.

The Supreme Court in a number of cases has upheld the view that Article 14 does not rule out classification for purposes of legislation. Article 14 does not forbid classification or differentiation which rests upon reasonable grounds of distinction.

The Supreme Court in the case of State of Bihar v. Bihar State ‘Plus-2’ lectures Associations, (2008) 7 SCC 231 held that now it is well settled and cannot be disputed that Article 14 of the Constitution guarantees equality before the law and confers equal protection of laws.

It prohibits the state from denying persons or class of persons equal treatment; provided they are equals and are similarly situated. It however, does not forbid classification.

In other words, what Article 14 prohibits is discrimination and not classification if otherwise such classification is legal, valid and reasonable. Space to write important points for revision

Question: Discuss the “Doctrine of Eclipse” under the Constitution of India.

Answer:

Doctrine of Eclipse:

The Doctrine of Eclipse is a part of Article 13 of the Constitution of India. It helps in empowering the fundamental rights.

According to this doctrine, if there is any act prevailing from before the pre-Constitution days, and it contains something that is against the Constitution, the act will not become redundant, but will be eclipsed or become dormant to that extent till the Constitution is amended so it can be operative again.

This saves parliamentary laws from being scrapped and remade, and whenever such eclipse is removed, the law is operative again from the date of such removal.

The doctrine came to light in the case of Bhikaji Narain Dhakras vs. State of M.P., which questioned the power of the Government to regulate, control and to take up the entire motor transport business by itself, by means of an Act.

The Act was initially valid, but after the Constitution came into being, it was rendered inconsistent under the provisions made by Article 13(1), on the grounds that it contravened the freedom to carry on trade and business given by the Constitution under Article 19(1)(g).

It was thereby held that in the case of a pre-Constitution law or statute, the doctrine of eclipse would apply. Although till date, no clear-cut decision has been made whether the Doctrine of Eclipse is applicable on just pre-Constitution laws or even on post-Constitution laws.

Question: Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India provides that all citizens shall have the right to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or Business. Explain.

Answer:

Article 301. Freedom of trade, commerce and intercourse under Article 19 (1) (g):

The Constitution provides that subject to the other provisions of this part, every person has the right to carry on any trade, commerce or intercourse throughout the territory of India.

Article 302. Power of Parliament to impose restrictions on trade, commerce and intercourse:

The Parliament may by law impose such statutory restrictions on the freedom of trade, commerce or intercourse between one State and another or within any part of the territory of India as may be required in public interest, safety or integrity of the country.

Article 303. Restrictions on the legislative powers of the Union and of the States with regard to trade and commerce:

The Union and the State can make any laws or restrict trade or business in any commodity in case there is a shortage or scarcity in any state or region, but other than this, there can be no discrimination between states.

Article 304. Restrictions on trade, commerce and intercourse among States:

The legislature of a state may impose any kind of tax on goods brought into that state from another state or union territory, in order to remove any extreme differences in the prices of commodities.

Freedom of trade and profession is provided under Article 19 (1) (g) of the Constitution of India. This gives the citizens the right to pursue any trade, profession, business or occupation in any place within India.

This right is, however, not absolute and it can be restricted by the State in the following cases –

- When the State feels it is essential to do so in the public interest.

- When it is felt that there should be some basic qualifications for any occupation or profession, it can provide so.

- When the State feels that it needs to establish control in some area of trade, occupation or business, so that it can be better tended.

These restrictions shall be considered valid when the conditions of the trade or business restricted at that time justify them, for example, for keeping the price of essential services down.

Hence, the State can take over these rights to any extent – from being one of the participants in that trade to being the only one, provided it is justified in doing so.

Question: Vijay, an accused, committed an offence of dacoity in 2015. At that time dacoity was punishable with imprisonment of 10 years. In 2016 during his trial, a law was passed which made dacoity punishable with life imprisonment. Which penalty would be applicable on accused Vijay’? Discuss the answer with reference to Article 20(1) of the Indian Constitution.

Answer:

Protection against ex-post facto laws:

According to Article 20(1), no one shall be convicted of any offence except for violation of a law that made the act committed an offence. Nor can a penalty greater than that which might have been inflicted under the law in force at the time of the commission of the offence be charged for the offence.

Ex-post facto laws:

These are laws which punish what had been lawful when done. The Constitution protects anyone who had committed an act earlier when the act was not punishable from being punished with retrospective effect.

If a particular act was not an offence according to the law at the time when the person did that act, then he cannot be convicted under a law which with retrospective declares that act as an offence.

For example, something done in 2000 which was not an offence then under any law cannot be declared as an offence under a law made in 2018 giving retrospective validity and adding applicability to it from a back date, say from 2000.

Similarly, the penalties for an offence too, cannot be enhanced with retrospective effect, so as to bring more punishment to bear upon someone who had committed an act against that law.

Shiv Bahadur Singh v. State of Vindhya Pradesh In this case, it was clarified that Article 20 (1) prohibited the conviction under an ex-post facto law, and that too the substantive law. This protection is not available with respect to procedural law.

Thus, no one has a vested right in procedure. Hence, Vijay cannot be punished with life imprisonment as that penalty was introduced in 2016, whereas the offence took place in 2015. So for him, the penalty would be ten years.

Question: “Any law which is inconsistent with the fundamental rights is void ‘to the extent of inconsistency’ and it is not necessary to strike down the whole Act as invalid, if only a part is invalid.” Discuss.

Answer:

Doctrine of Severability: Any law which is inconsistent with the Fundamental Rights is void to the extent of inconsistency: This Doctrine is contained in Article 13 of the Constitution of India. According to this doctrine, the part of a statute which is not compatible with the fundamental rights provided for in the Constitution will be severed and declared invalid.

This helps to maintain both constitutionality and saves the statutes from being struck down completely. The rest of the act that is allowed to exist can operate separately. The only thing to be considered here is whether the leftover portion is enough to still fulfill the objectives of the Act.

This doctrine is a very useful one, used in both contract and common law, as it is useful in saving redundancy of contracts. and acts. Under this, Courts construct the meaning of a contract or act by severing the troubling part, if it is severable and only if severability is not possible, the entire act is scrapped (Article 154).

Similarly, the courts have the power to sever an unconstitutional provision in a statute and enforce the remainder of the statute if it can exist without the severed part (Article 155). This doctrine has been provided to increase the usability of statutory acts and legal contracts, so as to prevent redundancy and to make future use possible.

In the case of A.K.Gopalan v. State of Madras, the Supreme Court ruled that where an Act was partly invalid, if the valid portion was severable from the rest, the valid portion would be maintained, provided that it was sufficient to carry out the purpose of the Act.

Question: “Under the Indian Constitution, Parliament is empowered to make law even on the subjects enumerated in the State List”. Discuss the power of Parliament to make Laws on State List.

Answer:

The Parliament can extend the legislative powers given to it by the Constitution to formulate laws under special situations to include certain subjects of the State List. Some of the conditions under which the Parliament may extend its powers include the situations explained below: sentad

- In the National Interest (Under Article 249)

- Proclamation of Emergency (Article 250) in any state by the President.

- If two states agree that the Parliament can legally make laws with respect to the two states, then the Parliament can make laws relating to any state or states (Under Article 252)

- For the implementation of treaties in the international interest of the country (Under Article 253).

- Failure of Constitutional Machinery in a State as a result of the stod inefficiency of a State Legislature, as declared by a proclamation issued by the President (Under Article 356 (1) (b).

Normally both the Union Government and the State Governments operate within the limitations of the powers given to them by the Constitution. They enjoy equal powers to make laws relating to the Concurrent list items, which are of general importance such as succession, transfer of property, preventive detention, education, etc.

If there arises a conflict between a law passed by the Union and that passed by one or more State Legislatures, precedence would be given to the law made by the Union Parliament.

However, problem arises when either the Union or a State illegally encroaches upon the powers of the other legislature, or they may arise because the two laws do not coordinate. Only where the legislation is on a matter in the Concurrent List, it becomes important to apply the test of repugnancy and judge which act will apply.

Normally the Union law is given preference, unless the State has reserved a law for the approval of the President, in which case it will supersede the law made by the Union. However, the Union can at all times cause an alteration or amendment in the law.

Question: Briefly describe the Fundamental Rights against exploitation under Constitution of India, ug say (5 marks)

Answer:

The Right against Exploitation is contained in Articles 23 and 24, which provide for rights against exploitation of citizens as well as non-citizens. The rights are ensured by way of certain restrictions, against the State as well as against private persons.

Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour:

Article 23 bans human trafficking, beggar and other similar forms of forced labour, seen in rural and interior parts of the country mostly. These articles term these practices unconstitutional and any person forced to suffer these practices can complain against the violation of his fundamental right under this article.

The exceptions here are the State which can impose compulsory services for public purposes such as for defence or for social service etc. However, in so doing, the State cannot discriminate on grounds of religion, race, caste or class.

Prohibition of employment of children: Article 24 bans the employment of children below the age of fourteen in 319 any factory or mine. Guidelines for this were given by the Supreme Court aab in the landmark case of M.C. Mehta v. State of T.N.

The topic is also pain detailed in various other acta that protect the rights of children, viz. the Employment of Children Act, 1938; The Factories Act, 1948; The Mines Act, 1952; The Apprentices’ Act, 1961; and the Child Labour (Prohibition onorand Regulation) Act, 1986.

Question: “Article 16 of the Indian Constitution guarantees equal opportunity to all citizens of India in matters related to public employment. However, there are certain exceptions of the Article 16”. Explain the reservation policy in India.

Answer:

If someone is denied public employment on grounds of his caste, religion or place of birth, he can use Article 16 of the Constitution of India for opposing such an action. Article 16 (1) gives every citizen equal rights to public employment, whereas Article 16(2) prohibits inequity in such matters.

In the case of Champakam Dorairajan vs. State of Madras, 1951, caste based reservations were struck down by the court, as against Article 16(2) of the Constitution.

If a citizen who seeks admission into any such educational institution has not the requisite academic qualifications and is denied admission on that ground, he certainly cannot be heard to complain of an infraction of his fundamental right under this Article.

This case resulted in the First Amendment of the Constitution of India.

The exceptions to this are provided in the Articles 16(3), 16(4), 16(4A), 16(4B), 16(5), & 16(6):

- The Parliament has every right to promulgate a law requiring residence of a particular State or Union Territory, in the context of employment or appointment to an office under the Government of a State on a Union Territory. In this case, such a condition shall be deemed to be an essential qualification for employment. [Article 16(3)]

- Likewise, the State can make reservations for a particular backward class of citizens which in its opinion, is not adequately represented in the State services. [Article 16(4)]

- Similarly, the Parliament can make reserve some specific posts for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes which, the State deems to be inadequately represented in the services under the State. [Article 16(4A)].

- The State has the authority to fill any unfilled vacancies in a particular year. For this purpose, they can consider the posts previously reserved for under Article 16 (4) or 16 (4A) as a separate class of vacancies that can be filled in the succeeding year(s). To this end, they will not be clubbed with the vacancies of that year. [Article 16(4B)].

- A law requiring that an incumbent to the office related to the affairs of a particular religious or denominational institution or that of its governing body shall compulsorily be a person from the same religion or denomination shall not be deemed to be invalid for this reason. [Article16(5)].

CS Executive JIGL – Constitution Of India Practical Questions

Question 1: Rajasthan Legislature passed a law restricting the use of sound amplifiers. The law was challenged on the ground that it deals with a matter which falls in entry 81 of List-I under the Constitution of India which reads: “Post and telegraphs, telephones, wireless broadcasting and other like forms of communication” and therefore, the State Legislature was not competent to pass it. Examine the proposition in the light of “Pith and Substance Rule” referring the case law on this point.

Answer: The Rule of Pith and Substance means that where a law in reality and substance falls within an item on which the legislature which enacted that law is competent to legislate, then such law shall not become invalid merely because it incidentally touches a matter outside the competence of legislature.

Acting on Entry 6 of List II of the Constitution of India which reads – Public Health and Sanitation, Rajasthan Legislature passed a law restricting the use of sound amplifiers.

The law was challenged on the Schedule VII, entrý 31 of List I of the Constitution of India deals with “Post and telegraphs, telephones, wireless broadcasting and other like forms of communication, and, therefore, the State Legislature was not competent to pass it.

The Supreme Court rejected this argument on the ground that the object of the law was to prohibit unnecessary noise affecting the health of public and not to make a law on broadcasting, etc.

Therefore, the pith and substance of the law was public health and not broadcasting (G. Chawla v. State of Rajasthan, AIR 1959 SC 544).