Circumstantial evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Circumstantial evidence is that derived from the surrounding facts. For example, if in a room, an attempt to murder has taken place, the state of the things in the room will be taken into consideration as circumstantial evidence.

For although, the state of things by itself is not sufficient proof that a murder took place, but it can strongly indicate to it, through the signs of struggle in the room, the sight of blood, a weapon lying on the ground etc. In the absence of primary evidence, circumstantial or secondary evidence can be relied upon to give an idea about the situation.

Res gestae in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 6 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 opines the inclusion of res gestae in a case as relevant facts. They can be defined as those facts that were although incidental to the main fact but were explanatory of it, and hence to be included as relevant facts.

They have to form part of the same transaction in order to be included within this definition. Res gestae is based on the belief that because certain statements are made naturally, spontaneously, and without deliberation during the course of an event, they carry a high degree of credibility and leave little room for misunderstanding or misinterpretation.

The doctrine held that such statements are more trustworthy than other secondhand statements and therefore should be admissible as evidence.

Primary evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Primary evidence’ as per the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 means the very document itself, not a copy of it. The provision of primary evidence is based on the ‘Best Evidence’ principle, i.e. if there is better evidence available, then that must be provided.

If the person capable of providing. superior evidence supplies an inferior one, it creates an unfavorable stance against him. (Section 62)

Secondary evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Secondary evidence’ means certified or compared copies of, or counterparts of, or oral accounts of documents. (Section 63) According to Section 65 of the Act, where primary evidence can be provided, secondary evidence should not be used.

It should only be given where the original document is not available because it has been lost or destroyed, or it is otherwise unavailable because it cannot easily be moved because of bulk, or because it is under the control of some public authority’s control.

Learn and Read More CS Executive JIGL Question and Answers

Opinions of experts in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 45 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 makes the opinions of experts important on points of specialized areas like handwriting analysis, fingerprints, artistic impressions, scientific principles and foreign legal positions.

Anyone possessing specialized knowledge in the above mentioned fields would be deemed to be an expert. Section 73 opines that comparison of signature, seal or handwriting of a

person is allowed to see whether they actually belong to the said person.

The Court may even ask that person to write before it in order to prove his handwriting. For this purpose, the help of an expert might be taken. The statement of an expert can even be admitted as evidence in documentary form without his presence being stressed upon; this is known as ‘hearsay evidence’.

Presumptions in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Presumptions are used in the interpretation of statutes only when the intention of the legislature is not clear; when it is clear, they are to be avoided. Conjecture or suppositions are used when it becomes difficult to comprehend the statute in its own light.

The basic presumptions used in the interpretation of statutes are as follows –

- The words used in the statute have been used in the literal sense with precise meanings unless otherwise defined.

- There has been effected no change in the rights of the people unless the statute prescribe such a change expressly.

- Liability only attaches where there is mens rea (guilty mind).

- The state or governmental institutions, unless expressly covered, are deemed to be exempted.

- The legislature, while passing the new statute was aware of the manner of functioning of the judiciary and the executive as well as the legal condition in the country and unless stated, has not caused any changes in it.

- No mistakes have been committed by the legislature in drafting the statute.

- No pointless activity would be enjoined on the people.

Facts in issue in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

According to Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, the expression “facts in issue” means and includes-any fact from which, either by itself or in connection with other facts, the existence, non-existence, nature or extent of any right, liability, or disability, asserted or denied in any suit or proceedings, necessarily follows.

Issue of fact in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Whenever, under the provisions of the law for the time being in force relating to Civil Procedure, any Court records an “issue of fact”, the fact to be asserted or denied in the answer to such issue is a “fact in issue”.

The principle of estoppel in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

The principle of estoppel implies that a person who states certain facts must not be allowed to state something contrary to the facts stated by him earlier.

It follows from the generally accepted rule that a person cannot approbate and reprobate at the same time. This is specially the case when another has relied on the information or statement given by one and done something that he otherwise would not have done.

This is to prevent undue hardship for others who depend on the statements previously made by that person.

Admissions in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Admissions’ have been defined in Section 17 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 as oral or documentary statements, or those in electronic form that imply or lead to any fact that is relevant or to any circumstances that are relevant.

Only those statements that fit the description given in Sections 18-20 are included in this definition.

Confessions in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Confessions’, on the other hand, are defined under Sections 24 to 30 of the Act. The term ‘confession’ has been defined by the Judicial Committee in Pakala Narayanaswami v. Emperor, 66 Ind App 66: (AIR 1939 PC 47):

“A confession is a statement made by an accused which must either admit in terms of the offence, or at any rate substantially all the facts which constitute the offence.”

Primary evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Primary evidence’ as per the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 means the very document itself, not a copy of it. The provision of primary evidence is based on the ‘Best Evidence’ principle, i.e. if there is better evidence available, then that must be provided.

If the person capable of providing superior evidence supplies an inferior one, it creates an unfavorable stance against him. (Section 62)

Secondary evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Secondary evidence’ means certified or compared copies of, or counterparts of, or oral accounts of documents. (Section 63). According to Section 65 of the Act, where primary evidence can be provided, secondary evidence should not be used.

It should only be given where the original document is not available because it has been lost or destroyed, or it is otherwise unavailable because it cannot easily be moved because of bulk, or because it is under the control of some public authority’s control.

Circumstantial Evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

‘Circumstantial Evidence’ is a kind of derived evidence, that can be gained from sources seen as secondary. For example, a copy of a document or a record in a public file can be taken as evidence in the absence of the original documents.

Another example could be that of the state of things in a particular room, where a crime has taken place. They can be considered when no eye-witness account is available.

Circumstantial or secondary evidence is used only in case the primary evidence is missing or unavailable.

Fact in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

According to Section 3, ‘fact’ means and includes:

- anything-either state of things or relation of things – capable of being perceived by the senses;

- any mental condition of which a person is aware. Facts can be of two types physical and psychological.

Relevant Fact in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

A fact can be said to be relevant to another when it is connected with the other in any of the ways referred to in Section 3 of this Act. Usually, in a case direct evidence is preferred.

If it is not available to prove a fact in issue, then circumstantial evidence may be resorted to and in such a case circumstantial evidence would also be a ‘relevant fact’.

Logical relevancy and legal relevancy in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

It includes facts holding logical relevance, i.e. facts that are so linked with other acts that they might affect their existence. Legal relevance of facts might be defined as the importance of some facts necessary to assert the existence or state of other facts.

Relevance depends on the case and the state of things. For example, a fact may be relevant for one case, but completely irrelevant for another.

Oral evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Spoken testimony that witnesses give in a court, usually upon oath. Oral evidence is always direct. “Oral evidence means statements which the court permits or requires to be made before it by witnesses in relation to matters of fact under inquiry.

But, if a witness is unable to speak he may give his evidence in any manner in which he can make it intelligible as by writing or by signs.” (Section 119)

Hearsay evidence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

It is evidence given by someone other than a witness, and that too, out of court. As a rule, it is not admissible as evidence. It is information received from someone else; not what the witness knows personally.

Estoppel by attestation in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

If a person attests a document with notice of its contents, only then his attestation would operate as an estoppel. Generally, this is not applicable.

Estoppel by contract in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Wen once a party has entered into a contract, they cannot later retract; it would be counted as a breach.

Constructive estoppel in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

It applies when the state of things is different from what it appears to be. For example, any documents pertaining to immovable property are necessarily registered because under the Transfer of Property Act, registration of a document operates as constructive notice of its contents.

Even though a person might not be aware of the contents of the sale deed or transfer or even of their existence, but he is deemed to have knowledge regarding them, if they are registered.

Estoppel by-election in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Such an estoppel is used when there are multiple gifts to the same person. He has to choose, as they are in the alternative; not all can be enjoyed. Once he has chosen, he cannot retract from his choice. It also means that a person cannot approbate or reprobate under the same instrument.

Equitable estoppel in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 116 of the Act deals with the estoppel that arises against a tenant or licensee. A similar estoppel has been said to arise against a mortgagee, an executor, a legatee, a trustee, or an assignee of property that forbears him from denying the title of the mortgagor, the testator, the author of the trust, the assignor, etc.

It can also be defined as an estoppel that is not covered by the Evidence Act.

Estoppel by negligence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Such estoppel leads another party dealing with a party or operating under a contract to claim property that in fact, the other party does not own. Such estoppel is known as estoppel by negligence or by conduct or representaton or by a holding out of ostensible authority.

Estoppel by silence in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Such estoppel arises in situations that demand or require a duty to speak or disclose some facts. This estoppel stops a party from claiming or asserting that he could have claimed when he had the right earlier, but did not, in fact, so claim.

His not claiming it earlier put another party at a disadvantage, hence he is stopped from making the claim later.

Indian Evidence Act, 1872 Distinguish Between

Question 1: Distinguish between ‘Admission’ and ‘Confession’ under Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Answer:

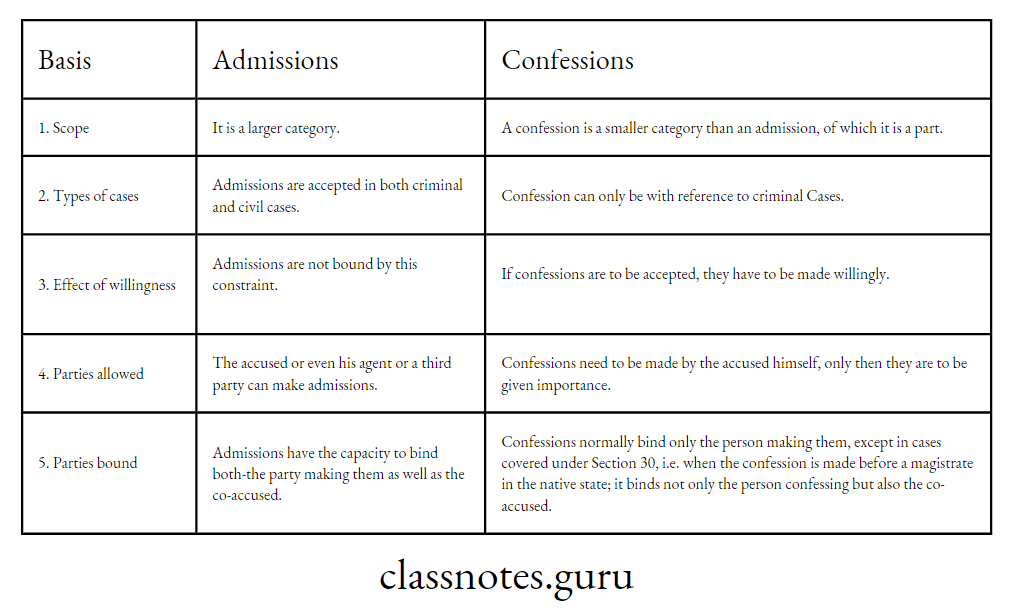

‘Admissions’ have been defined in Section 17 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 as oral or documentary statements, or those in electronic form that Imply or lead to any fact that is relevant or to any circumstances that are relevant.

Only those statements that fit the description given in Sections 18 to 20 are included in this definition. ‘Confessions’, on the other hand, are defined under Sections 24 to 30 of the Act.

The term ‘confession’ has been defined by the Judicial Committee in Pakala Narayanaswami vs Emperor, 66 Ind App 66: (A.I.R 1939 P.C. 47): “A confession is a statement made by an accused which must either admit in terms of the offence, or at any rate substantially all the facts which constitute the offence.”

Their differences are as follows:

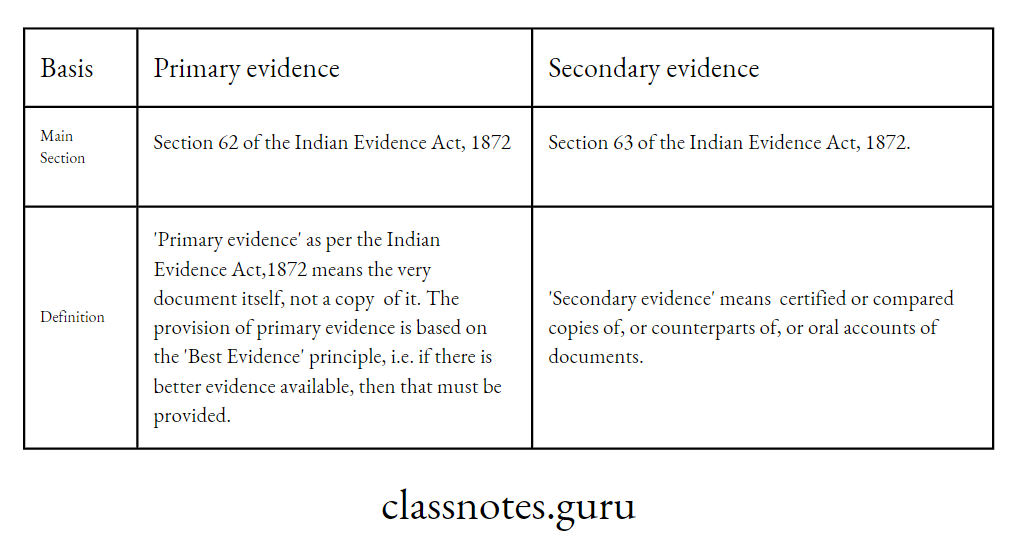

Question 2: Distinguish between ‘Primary Evidence’ and ‘Secondary Evidence’ under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Answer:

Difference between ‘Primary Evidence’ and ‘Secondary Evidence’ under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Indian Evidence Act, 1872 Descriptive Questions

Question 1: Explain the following: need (iv) ‘Expert opinion’ under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Answer:

‘Expert opinion’ under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Expert opinion under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 24199 This is covered under Sections 45 to 51 in the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

They prescribe as under –

Section 45 This makes the opinions of experts important on points of specialized areas like handwriting analysis, fingerprints, artistic impressions, scientific principles and foreign legal positions.

Anyone possessing specialized knowledge in the above mentioned fields would be deemed to be an expert. However, the court is not bound by the opinion of the expert. It might or might not give weightage to the opinion of the expert while adjudicating the issue.

This is allowed since an expert has detailed knowledge vis-à-vis a judge who is not equipped with the technical knowledge and hence not capable of drawing inferences from the facts presented before him.

For example – An expert can be considered when the analysis of someone’s handwriting is to be done, or when it is to be found whether someone was killed by a particular poison.

Question 2: What is ‘documentary evidence’ under Indian Evidence Act, 1872? Explain briefly.

Answer:

Documentary evidence:

Document: It means and includes any written matter, or matter recorded upon any material by way of letters, figures or marks, or by multiple means. The documents that are produced for the inspection of a Court are known as documentary evidence.

Examples of such could be copies of deeds, receipts, signed agreements etc. Such evidence is classified as Primary and Secondary evidence.

Primary Evidence is the document itself (Section 62 of the Evidence Act, 1872). The production of such documents follows the rule that if a better or the best evidence is present that should be given in evidence.

This enhances the credibility of the evidence. Conversely, if inferior evidence is offered, it will reflect negatively on the person giving it to the Court.

Secondary evidence, on the other hand, includes the certified or compared copies, or those made with the help of some mechanical process (Section 63). Even oral accounts of documents and photographs of the original are acceptable in this category.

Section 65 of the Act provides that usually primary evidence must be given, but where it is not available, secondary evidence may be resorted to, like in cases where the primary evidence has been destroyed or is not readily available or movable.

Question 3: Explain in brief ‘Principle of Estoppel’ under Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Answer:

‘Principle of Estoppel’ under Indian Evidence Act, 1872

The Principle of Estoppel is covered in Chapter VIII of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Section 115 says that when a person declares or leads others to believe a fact or thing to be true, he and his legal representatives are stopped from denying its non-veracity afterwards.

Section 116 says that tenant or anyone claiming under him cannot deny the title of the landlord during the period of his tenancy. Same is the case with a license, when a person to whom it was given cannot deny that the person who gave it does not possess proper title during the continuance of the license.

Section 117 pronounces that an acceptor of a bill of exchange cannot deny that the drawer had no authority to draw or endorse if he has accepted it without demurring earlier. The same condition would apply to a bailee and licensee.

The conditions in which this principle is applied are when a person is alluding to contrary facts at the same time, as a person cannot be allowed to approbate and reprobate at the same time.

Question 4: The ‘Privileged Communications’ are based on Public Policy and a witness cannot be compelled to answer the same during the evidence in the Court or before any other authority. Explain in brief.

Answer:

The ‘Privileged Communications’ are based on Public Policy and a witness cannot be compelled to answer the same during the evidence in the Court or before any other authority.

There are some facts of which evidence cannot be given though they are relevant, such as facts coming under Sections 122, 123, 126 and 127 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, where evidence is prohibited.

They are also referred to as ‘privileged communications’. A witness though compellable to give evidence is privileged in respect of particular matters within the limits of which he is not bound to answer questions while giving evidence.

These are based on public policy and are (i) Evidence of a Judge or Magistrate in regard to certain matters (Section 121) (ii) Communications during marriage (Section 122) (iii) Affairs of State (Section 123) (iv) Official Communications (Section 124) (v) Source Information of a Magistrate or Police Officer or Revenue Officer as to commission of an offence or crime (Section 125) (vi) In the case of Professional Communication between a client and his barrister, attorney or other professional or legal advisor (Sections 126 and 129).

But this privilege is not absolute and the client is entitled to waive it.

Under Section 122 of the Act, communication between the husband and the wife during marriage is privileged and its disclosure cannot be enforced. This provision is based on the principle of domestic peace and confidence between the spouses.

Question 5: ‘Confession caused by inducement, threat or promise is irrelevant’. Explain briefly. (4 marks)

Answer:

According to Section 24 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 confession caused by inducement, threat or promise is irrelevant. To attract the prohibition contained in Section 24 of the Evidence Act the following six facts must be established:

- that the statement in question is a confession

- that such confession has been made by an accused person

- that it has been made to a person in authority

- that the confession has been obtained by reason of any inducement, threat or promise proceeded from a person in authority such inducement, threat or promise, must have reference to the charge against the accused person

- the inducement, threat or promise must in the opinion of the Court be sufficient to give the accused person grounds, which would appear to him reasonable for supposing that by making it he would gain any advantage or avoid any evil of a temporal nature in reference to the proceedings against him.

To exclude the confession it is not always necessary to prove that it was the result of inducement, threat or promise. It is sufficient if a legitimate doubt is created in the mind of the Court or it appears to the Court that the confession was not voluntary.

It is however for the accused to create this doubt and not for the prosecution to prove that it was voluntarily made. A confession if voluntary and truthfully made is an efficacious proof of guilt.

Question 6: Opinion of experts under section 45 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Answer:

Section 45 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 deals with opinions of experts. It provides that when the Court has to form and opinion upon a point of foreign law or of science or art, or as to identity of handwriting or finger impressions, the opinions upon that point of persons specially skilled in such foreign law, science or art, or in questions as to identity of handwriting or finger impressions are relevant facts.

Such persons are called experts. Illustrations The question is, whether the death of A was caused by poison, The opinions of experts as to the symptoms produced by the poison by which A is supposed to have died, are relevant.

The question is, whether A, at the time of doing a certain act, was, by reason of unsoundness of mind, incapable of knowing the nature of the Act, or that he was doing what was either wrong or contrary to law.

The opinions of experts upon the question whether the symptoms exhibited by A commonly show unsoundness of mind, and whether such unsoundness of mind usually renders persons incapable of knowing the nature of the acts which they do, or of knowing that what they do is either wrong or contrary to law, are relevant.

The question is, whether a certain document was written by A. Another document is produced which is proved or admitted to have been written by A.

The opinions of experts on the question whether the two documents were written by the same person or by different persons are relevant.

Question 7: Explain the special provisions as to Evidence relating to Electronic Record under the provisions of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Answer:

The special provisions as to Evidence relating to Electronic Record under the provisions of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 65A of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 provides that the contents of electronic records may be proved in accordance with the provisions of Section 65B.

As per Section 65B(1) of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, any information contained in an electronic record which is printed on a paper, stored, recorded or copied in optical or magnetic media produced by a computer (hereinafter referred to as the computer output) shall be deemed to be also a document, if the conditions mentioned in this Section are satisfied in relation to the information and computer in question and shall be admissible in any proceedings, without further proof or production of the original, as evidence of any contents of the original or of any fact stated therein of which direct evidence would be admissible.

The conditions in respect of a computer output related above, have been stipulated under Section 65B (2) of the Evidence Act.

Question 8: Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 deals with the term ‘Evidence’. Explain it. (4 marks)

Answer:

According to Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which is the ‘interpretation clause’, the definition of ‘evidence’ includes the following:

Oral evidence statements which the Court permits or requires to be made before it by witnesses, relating to matters under inquiry.

Documentary evidence documents including electronic records produced for the inspection of the Court.

The expression “facts in issue” means and includes-any fact from which, either by itself or in connection with other facts, the existence, non-existence, nature or extent of any right, liability, or disability, asserted or denied in any suit or proceedings, necessarily follows.

Whenever, under the provisions of the law for the time being in force relating to Civil Procedure, any Court records an “issue of fact”, the fact to be asserted or denied in the answer to such issue is a “fact in issue”.

A “fact in issue” is called as the principal fact to be proved or factum probandum and the relevant fact the evidentiary fact or factum probans from which the principal fact follows. The fact which constitutes the right or liability called “fact in issue” and in a particular case the question of determining the “facts in issue” depends upon the rule of the substantive law which defines the rights and liabilities claimed.vn

Under Civil Procedure Code, the Court has to frame issues on all disputed facts which are necessary in the case. These are called “issues of fact’ but the subject matter of an issue of fact is always a “fact in issue”. Thus, when described in the context of Civil Procedure Code, it is an “issue of fact’ and when described in the language of Evidence Act it is a “fact in issue”.

Question 9: When the opinion of any person is relevant except experts under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872?

Answer:

This is covered Under Sections 45 to 51 in the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. They prescribe as under:

Section 45-This makes the opinions of experts important on points of specialized areas like handwriting analysis, fingerprints, artistic impressions, scientific principles and foreign legal positions. Anyone possessing specialized knowledge in the above mentioned fields would be deemed to be olent to an expert.

Section 46- Facts that provide support to the opinions mentioned in Section 45 will also be relevant, oriolowW

Section 47-In case of an opinion regarding handwriting verification, the opinion of someone who was familiar with it would be relevant.

Section 47A -When it is a case of identifying someone’s digital signature, the opinion of the Certifying Authority under the Information Technology Act,

2000 would be a relevant fact.

Section 48 -When it is a question of establishing facts regarding existence of a right or custom, the opinion of someone who knows about them would be relevant.

Section 49-When it is a matter of opinion regarding meaning of words or particular terms and their usages in certain areas, or the set-up or running of a religious/charitable foundation, the opinion of a person who knows facts regarding them would be deemed to be relevant.

Section 50 -When it is a question of the relationship between two persons, i.e. its existence or nature, the opinion of someone who knows facts about it would be relevant.

Section 51-When an opinion is considered relevant, the facts it is based on also become relevant.

Question 10: Extra-Judicial confession was made before a witness who was a close relative of accused and the testamony of said witness was reliable and truthful. Examine the relevancy of this confession.

Answer:

In Vinayak Shivajirao Pol v. State of Maharashtra’s case, the Supreme Court has held that the law does not require that the evidence of an extra-judicial confession should be corroborated in all cases.

When such confession is proved by an independent witness who is a responsible officer and one who bears no animus against the accused, there is hardly any justification to disbelieve it.

Also, where the Court finds that the confession made by the accused to his close relative was unambiguous and unmistakably conveyed that the accused was the perpetrator of the crime and the testimony of said close relative was truthful, reliable and trustworthy, a conviction based on such extra-judicial confession is proper and no corroboration is necessary.

Much importance could not be given to minor discrepancies and technical errors. It was determined in the case of Ram Khilari v. State of Rajasthan by the Supreme Court that “where an extra-judicial confession was made before a witness who was a close relative of the accused and the testimony of said witness was reliable and truthful, the conviction on the basis of extra judicial confession is proper.”

Question 11: What is Professional Communications? In a case Ramesh, a client, says to Ashwin, his Advocate, “I stole a bike and I whish you to defend me” Ashwin refused to plead his case. Later on Ashwin gives evidence against Ramesh about this communication. Is this communication protected from disclosure under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872? Explain.

Answer:

Sections 126 to 129 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 deal with privileged communications, i.e. between a legal adviser and a client. Such communication is protected from disclosure, and the client cannot be forced to disclose the information he has communicated to his lawyer or legal adviser. However, if the client himself gives his express consent, the information can be disclosed.

The rule has been made to aid the unhindered communication between client and lawyer, to further the interests of the legal relationship between them. This covers both oral and documentary communications between the two parties.

Under Sections 126 and 127 a legal adviser i.e. a barrister, attorney, pleader and vakil (Section 126) and his interpreter, clerk and servant (Section 128) are all covered.

In this case, Ramesh says to Ashwin, his advocate, that he stole a bike and that he wants him to take up his case, which Ashwin refuses. Later on, Ashwin cannot give evidence against Ramesh for this same offence.

This would only be permitted if Ramesh had given his express approval for the same. If not, the communications between the two are protected under the Indian Evidence Act.

Indian Evidence Act, 1872 Practical Questions

Question 1: Ragini told Rajendra in the year 2007 that she had committed theft of the jewellery of her neighbour Asha. Thereafter, Ragini and Rajendra were married in the year 2008. In the year 2009, criminal proceedings were instituted against Ragini in respect of the theft of the said jewellery. Rajendra is summoned to give evidence in the said criminal proceedings. Decide whether Rajendra can disclose the communication made to him by Ragini in the year 2007, in the criminal proceedings in respect of the theft of the jewellery.

Answer:

Section 122 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 says that no one can be compelled to disclose private conversations with his/her spouse that took place during marriage, as the information is privileged information. This can be done with the consent of the spouse.

According to the case of Nagaraj vs. State of Karnataka, Section 120 allows a spouse to bear witness against a spouse if the case is not between them, or does not arise out of criminal prosecutions. However, the privilege under

Section122 of the Indian Evidence Act extends to all communications made to a spouse during subsistence of marriage; the communication need not be confidential. Moreover, the privilege is not accorded to the witness, but to the spouse.

in M.C. Verghese v. T J. Ponnam it was said that if the marriage was subsisting at the time when the communications were made, the bar prescribed by Section 122 will operate. In Moss v. Moss 15 it was held that in criminal cases, subject to certain common law and statutory exceptions, a spouse is incompetent to give evidence against the other, and that incompetence continues after a decree absolute for divorce or a decree of nullity. ho

Hence, such a communication cannot be treated as privileged information, and Rajendra can disclose such communication made to him by Ragini. Space to write important points for revision

Question 2: ‘A’ is accused of the murder of ‘B’ by beating him. Discuss the rule of relevancy of fact of the statement said or done by ‘A’ or, ‘B’ or the bystanders at the beating, or so shortly before or after it.

Answer:

Relevant Fact:

A fact can be said to be relevant to another when it is connected with the other in any of the ways referred to in Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Usually in a case direct evidence is preferred.

If it is not available to prove a fact in issue, then circumstantial evidence may be resorted to and in such a case circumstantial evidence would also be a ‘relevant fact’. Relevance depends on the case and the state of things. For example, a fact may be relevant for one case, but completely irrelevant for another.

Section 6 embodies the rule of admission of evidence relating to what is commonly known as res gestae, and stresses on the inclusion of res gestae in a case as relevant facts. They can be defined as those facts that were although incidental to the main fact but were explanatory of it, and hence to be included as relevant facts.

They have to form part of the same transaction. in order to be included within this definition. Secondhand statements considered trustworthy for the purpose of admission as evidence in a lawsuit when repeated by a witness because they were made spontaneously and concurrently with an event.

Res gestae describes a common-law doctrine governing testimony. Under the Hearsay rule, a court normally refuses to admit as evidence statements that a witness. Traditionally, two reasons have made hearsay inadmissible: unfairness and possible inaccuracy.

Allowing a witness to repeat hearsay does not provide the accused with an opportunity to question the speaker of the original statement, and the witness may have misunderstood or misinterpreted the statement. Thus, in a trial, counsel can object to a witness’s testimony as hearsay.

Res gestae is based on the belief that because certain statements are made naturally, spontaneously, and without deliberation during the course of an event, they carry a high degree of credibility and leave little room for misunderstanding or misinterpretation.

The doctrine held that such statements are more trustworthy than other secondhand statements and therefore should be admissible as evidence.

Hence, when in this case, A is accused of the murder of B by beating him, things said or done by A or B or the by-standards at the beating, or before or after form part of the transaction, and are hence relevant facts.

Indian Evidence Act, 1872 Descriptive Questions

Question.1: Explain the principle of estoppel.

Answer:

The principle of estoppel

The Principle of Estoppel is covered in Chapter VIII of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Section 115 of this chapter says that when a person declares or leads others to believe a fact or thing to be true, he and his legal representatives are stopped from denying its non-veracity afterwards.

Section 116 says that tenant or anyone claiming under him cannot deny the title of the landlord during the period of his tenancy. Same is the case with a license, when a person to whom it was given cannot deny that the person who gave it does not possess proper title during the continuance of the license.

Section 117 pronounces that an acceptor of a bill of exchange cannot deny that the drawer had no authority to draw or endorse if he has accepted it without demurring earlier. The same condition would apply to a bailee and licensee.

The conditions in which this principle is applied are when a person is alluding to contrary facts at the same time, as a person cannot be allowed to approbate and reprobate at the same time.